As epiphanies go this is the biggest one I’ve ever had and it has had a drastic effect on just about everything I do, it has pushed and inspired me and continues to do so. It happened the place much of my learning happens…on a skid pad in a vehicle dynamics area. It had happened before, in fact many times but now the pattern was too prevalent to ignore, this wasn’t isolated or random it was common enough now that I knew what I was looking for that I had realized it was actually normal. People have no real idea of what they are good at or bad at. They are convinced they do but they don’t. It’s not all wrong, but it’s more wrong than right.

People have expectations, they come to me to teach them how to drive and they carry these expectations. On one end of the scale some naturally think they are “gifted”, showing up merely for confirmation of what they know to be true, others, the other end of the scale who really need training because think they are terrible, hopeless, unteachable or suffering from mental trauma from a prior crash. Many of course are somewhere in between. What do almost all of them have in common? In almost every case they, at least to some level, are wrong.

This is strange right? Why do I spend so much time trying to convince people of their truth doing this one thing? This made me wonder if they were as inaccurate in other aspects of their lives(?). The first thing I do in these situations is realize I am the same, though not in driving, you see I can’t hide my driving, it is tested and retested nearly every day of my life for the last several decades, driving is the one place the truth has to live for me but for others they rarely if ever get tested, not until they met me (or my equivalent in this or another endeavor) and they were all over the map with their expectations rarely being their reality. This means in every other aspect of my life I have no idea of my potential, I only think I do.

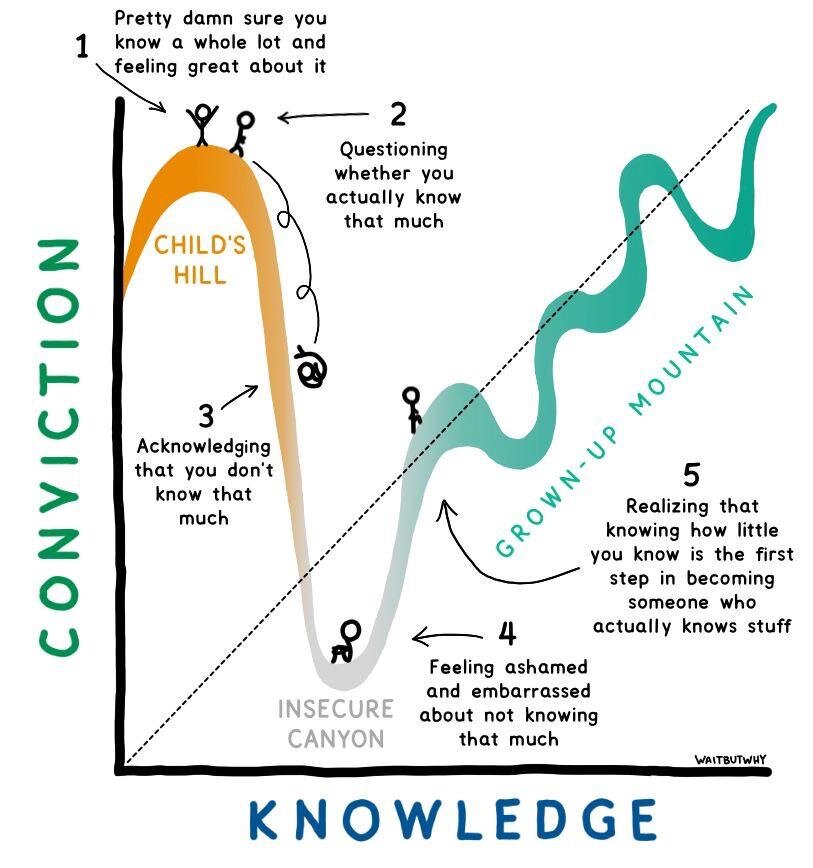

This one hit deep as it became clear how poorly we actually know ourselves, all of us. Unless it is something like driving for me, something you do daily under peer review, out in the open held to high standards. How many things in our lives are like that? If any at all for a sizable chunk of the population. That got me thinking about myself and everyone else and how this affects our ability to see let alone reach our potential. I started asking questions on the skidpad, why they “knew” they were good or bad. Many couldn’t pin point the why, more their expectation was more of just a feeling “I’m always good at stuff like this” or of course “I’m never good at stuff like this” but why did they have that feeling? Of course, we would easily reply because of past similar experiences which does make sense until you keep digging or get actual example from people on why they feel the way they do. What you end up discovering is that it’s mostly an accidental lie we tell ourselves, lie may be a little strong or unfair so let’s go with assume instead. So, we assume we know ourselves, does that to you sound plausible(?) or maybe better still you’re now thinking “no way, not me!”?

Perception is reality. To simplify our existence we take these assumptions seriously, from places to food to people and yes our own abilities (strengths/weaknesses), we are above all things creatures of habit, once we’re OK with any of these assumptions about literally anything we take it onboard and ingrain it, we make it part of who we are, we believe in and we don’t take the time to question it, we just move on to the next thing. We do this our whole lives, this is where curiosity, dreams and child-like glee go to die. This is depressing, this is on some level what everyone (myself included) is like. This self-belief system we rely on every day for every decision based on, at very best, incomplete information. Once it is ingrained we will never think to question it, it is part of our permanent programming…until, maybe one day, you meet someone like me randomly on a skid pad.

I feel like I’m writing a screenplay for the next Christopher Nolan blockbuster. This is in fact a bit mind bending and weird. Funny even if our lives weren’t so short and finite. Our potential is maybe the thing we should cherish the most, doesn’t self-improvement bring us arguably the most satisfying sensations possible? Yet we treat our potential without a second thought based at best on assumptions protecting our propped-up egos. We tell ourselves “it’s fine, everything’s fine” it’s not, we can all do so much more than we think and within any of it we have unlimited potential…as long as we don’t get in our own way.

So, where does it all come from? It is experiences, that much is true. How we were exposed to something, was that experience positive or negative? We categorize these experiences mostly subconsciously based on our senses and emotional reactions to those sensations. I’ve used the example of teachers before, they, like parents, siblings and friends are the most influential people in our lives. Who we are is greatly a result of this group of people. Anyone in this group can have this sort of influence on you but teachers are the clearest example. They come in all types and they teach all types of things. It’s a lottery. What I mean by that is that who you are today, many of the fundamental things you currently like/dislike (and usually also proportionally think you have an aptitude for) is nearly completely dependent on…drumroll…whether you personally connected with that teacher or not, that’s it, it has very little to do with that topic in particular, it could have been any topic and just because of that connection you will go your entire life thinking, believing, knowing that topic (not that teacher) is something you like and therefore are good at it. Self-fulfilling prophecy, those are the topics you lean into and become proficient at. A great teacher did that for you. Unfortunately, they are rare, just like great doctors and great anything for that matter.

We can and do have other things we have learned with enthusiasm and zeal from a great mom or dad or friend or any other strong influence in our life. So, this feel good portion of my Christopher Nolan film is drawing to a close because the rest of it is the issue at hand. As mentioned great anything is rare (and we are talking about why, this “screenplay” is practically writing itself while simultaneously feed on itself, I warned you it was weird!). It’s now time to address the real issue created by greatness being so rare and what that does to us. For every topic in the known universe that you didn’t have a great teacher for, you have no realistic idea where you stand. This is why we are so wrong about our potential, we assume it’s a lack of aptitude for a topic where in reality the reason the subject matter doesn’t seem compelling/interesting/relevant is because the wrong (not great) person is trying and failing to engage you on that topic. Meaningful anything comes from meaningful people. It has never been about the topic (which we generally remember, positively or negatively) but about the people who tried to teach it (who we generally forget or give too little credit to). We are emotional beings, we are always drawn to that engaging connection.

What does this all mean? First, great teachers should be respected and cherished by society, that tiny percentage of teachers have lasting influence on all they expertly interact with. Second, question everything about yourself, it’s never too late to be that kid again, bust out that nearly forgotten dusty dream, try new things and most of all have an open mind. Fail gloriously and laugh about it (but learn from it too). Seriously, stop adulting and above all else never stop reaching for your potential because it can carry you to greatness, then be meaningful, we’re all counting on you